As a society, we often focus on the power of medicine to heal people. Even the best technological breakthrough may be limited in its effectiveness if the socioeconomic and environmental factors of one’s life are not considered in the treatment plan. External factors, separate from the healthcare system, impact one’s ability to heal and be healthy. Social determinants of health (SDOH) are an integral part of treating patients. Addressing patient care from a holistic perspective leads to better health and well-being outcomes.

What are social determinants of health (SDOH)?

The National Academy of Medicine estimated that medical care accounts for only 10-20 percent of modifiable contributors to health outcomes. So, what impacts 80 percent of health outcomes? It’s SDOH.

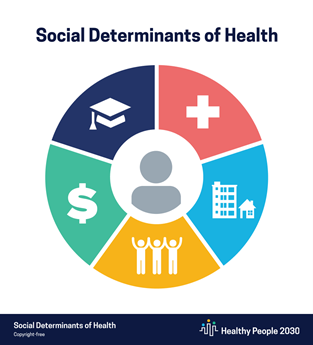

Healthy People 2030 defines SDOH as the conditions where you’re born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that impact one’s health, risks, and quality-of-life.

These factors help explain some of the causes of health disparities. That’s a difference in health outcomes and incidences depending on race/ethnicity, sex, age, sexual orientation, language and culture, disability status, or educational background.

SDOH can impact quality of life, health outcomes, risks, and how long you live.

It’s vital to address five main areas of SDOH to close the gap and create opportunities for optimal health outcomes at home, school, work, neighborhoods, and within communities. Healthy People 2030 focuses on five areas of SDOH and has goals for each one. They are:

- Economic stability

- Goal: Help people earn steady incomes so they can meet their health needs.

- Lower poverty rates.

- Increase employment in working-age people.

- Reduce the number of students who don’t go to school or don’t work.

- Increase the number of children with at least 1-full time working parent.

- Lower the proportion of families who spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing.

- Reduce food insecurity and hunger.

- Lower work-related injuries.

- Education access and quality

- Goal: Increase educational opportunities and improve school outcomes.

- Increase graduation rates and college attendance.

- Improve educational skills like reading and math.

- Provide access to preventive mental healthcare in school for more children.

- Improve access to intervention services.

- Social and community context

- Goal: Increase social and community support.

- Reduce the proportion of kids who have a parent or guardian who has been in jail.

- Lower anxiety and depression in caregivers of people with disabilities.

- Prepare foster care adolescents better for adulthood.

- Give children access to an adult they can talk to about serious problems.

- Improve health literacy.

- Reduce bullying of transgender students.

- Eliminate food insecurity.

- Healthcare access and quality

- Goal: Increase access to timely, comprehensive, and high-quality healthcare services.

- Increase the number of adults who get preventive care, every year.

- Improve cancer screenings.

- Increase early intervention programs.

- Neighborhood and built environment

- Goal: Create neighborhoods and environments that promote health and safety.

- Reduce violent crime among young adults and minor populations.

- Improve the digital divide.

- Lower air pollution and health and environmental risks from hazardous sites.

- Improve the water supply so it’s safe and has enough fluoride.

- Reduce car crash deaths.

- Improve physical activity.

- Reduce asthma deaths, attacks, and hospitalizations.

- Decrease tobacco use through policies like smoke-free restaurants and bars.

Healthy People 2030 wants everyone to attain their “full potential for health and well-being.”

It’s difficult, though, to prioritize one’s health when struggling with basic needs like food, safety, transportation, and social isolation.

For some individuals, the emotional, mental, and financial stress of daily life makes it challenging to establish healthy habits and manage health complications.

So, how prevalent are SDOH in impacting health outcomes?

In the McKinsey 2019 Consumer Social Determinants of Health Survey of individuals without an employer-sponsored health plan, 53 percent of respondents were adversely affected by at least 1 SDOH.

Food security was the most commonly reported unmet need, but often there were multiple needs.

SDOH example

Obesity is a paradox of food insecurity. Studies have found food-insecure adults may be at an increased risk for obesity. Studies on children yield the same result. It’s associated with fluctuations in eating habits and the low cost of energy-dense foods.

Some cases of obesity can be attributed to the inability to afford or access healthy food. In some zip codes, there are food deserts (areas where there is limited access to a variety of healthful foods due to a limited income or living far away from sources of wholesome and affordable food) and food swamps (communities where fast food and junk food are overwhelmingly more available than healthy alternatives). Cultural differences can also be a contributing factor to obesity.

A holistic approach to curbing obesity, that takes into account socioeconomic conditions, can yield the best results.

According to the McKinsey study, patients are open to trying new programs to bridge the gap in health disparities. Eighty-five percent of individuals with multiple unmet needs reported they would use a social program offered by their health insurer.

Close to half also said they’d participate in programs that offer discounts to buy healthy foods, free memberships at the gym, a wellness dollar account, home improvement reimbursements to address health concerns, and low-cost or no-cost drop-in care clinics.

When social programs are considered in combination with medical treatment, there’s greater potential to decrease health disparities. It takes a holistic approach and cooperative partnerships to achieve health equity for a community.

Health and quality of life outcomes

There are a number of federal, state, and local programs to address SDOH.

Some researchers argue we could close the gap by treating zip codes before treating diseases. With robust data reporting and analysis, health officials can identify zip codes most at risk for certain health conditions.

In the Wharton article, Ginger Pilgrim, Connie Yang, and Kelechi Nwoku found a 20-year disparity in life expectancy across US counties, and the gap is growing.

People tend to live to age 87 in Marin County, California, outside San Francisco and Summit County, Colorado, near the resort town of Breckenridge. Why? They’re highly educated, affluent communities. Plus, there’s a lot of green space in Summit County and some in Marin County, enabling a healthier lifestyle.

On the other end of the spectrum, the life expectancy is 67 in McDowell County, West Virginia, and Owsley County, Kentucky. Access to healthcare and incomes are significantly less in that part of the country, and poverty and chronic disease burden are significantly higher. In McDowell County, just getting water that’s safe to drink is a daily struggle.

The vast differences in culture, population density, weather, and demographics present different health outcomes from East to West and North to South.

For example, chronic disease indicators of those older than age 65 indicate diabetes is prevalent in about a third (30 percent) of the population living in northern states like Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa, South Dakota, and North Dakota.

Diabetes rates increase to 38-48 percent of the population if you head west to Wyoming or south to Oklahoma, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee, Kentucky, or West Virginia.

A one-size-fits-all approach typically will not work, as needs vary from state to state and city to city.

A community approach to well-being helps increase the ability and likelihood of addressing the specific needs of that community.

Local health systems play a vital role in evaluating and treating the social determinants of health through policy, strategic partnerships, and taking accountability for the health of the whole person.

Health disparities in asthma

On the local level, communities can change the conditions that affect one’s health. Neighborhoods are one of the SDOH.

Structural racism shaped many housing policies and led to segregated neighborhoods that still exist today. A study in The Lancet points out these conditions contribute to poorer health outcomes and an increase in chronic conditions. From disparate birth outcomes to increased rates of exposure to pollution and toxins, the environment in which one grows up can directly impact health.

Many African Americans and Latinx communities are densely populated areas with greater exposure to air pollution, substandard housing, limited opportunities for good jobs and high-quality education, fewer grocery stores, more food deserts and food swamps, greater reliance on public transportation, and fewer hospitals and health systems.

For example, asthma is a common health disparity. Black, Latinx, and Indigenous peoples in the U.S. (Native Americans/Alaska Native) individuals have the highest asthma diagnoses, deaths, and hospitalizations in the U.S. according to the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America. Black Americans are 1.5 times more likely to have asthma than whites. For Puerto Ricans, the risk is 2 times higher.

The need for emergency care is also greater. Black Americans are five times more likely to go to the ER due to asthma and 3 times more likely to die.

Despite policy and health care improvements over the last 15 years, the gaps in asthma outcomes are unchanged.

What’s driving this disparity? Studies show housing is the main SDOH contributor.

Individuals living in poverty are more likely to be exposed to air and water pollution, live in noisier areas, and more crowded homes.

Inadequate housing can increase indoor allergen exposure like mites, mold, and cockroaches which can trigger asthma and increase its morbidity and mortality. Inadequate ventilation in the home can mean high concentrations of tobacco smoke if there are smokers in the household and both particulate matter and diesel fuel if located near a highway or high traffic area.

When treating patients, some healthcare practitioners are asking questions about housing. In Chicago, community health workers made home visits as part of their program to help children breathe and thrive. The result – an 83 percent decrease in emergency room visits and a 75.8 percent decrease in the use of urgent care.

Holistic care takes a strategic and coordinated effort that puts patients first, values their lives holistically, and takes into consideration socioeconomic factors that may impact treatment plans and ultimately health outcomes.

Holistic, patient-centered care

There’s still a lot of work to be done to move beyond treating symptoms and treating the patient holistically.

A 2017 survey found a majority of physicians (69 percent) thought SDOH were not their responsibility nor that of the insurer. Ninety-one percent of physicians told the Salt Lake City-based healthcare intelligence firm, Leavitt Partners, it also wasn’t their job to help with affordable housing.

Yet, affordable housing access makes a significant difference.

The Lancet used the New York City Housing and Neighborhood Study as a case study. Individuals who won New York City’s affordable housing lottery had reductions in depression and asthma exacerbations.

Perspectives need to change. That’s just the first step.

Addressing SDOH takes a strategic approach and strong partnerships, investment and long-term time horizon, and strong partnerships.

Even among physicians who thought it was their responsibility to help with SDOH, 48 percent told Leavitt Partners they were not in a position to do anything about affordable housing.

The survey found the fee-for-service model, where there is an incentive to do more and spend less time with patients, impacted one’s ability to address SDOH.

There are many contributory factors, including insufficient time allocated to appointments to ask the right questions and make the appropriate referrals, inadequate infrastructure to provide housing support to patients, and insufficient social worker resources.

It takes a coordinated approach to address a patient’s underlying needs. One doctor can’t do it alone. Neither can one health system. But, when it’s a coordinated effort the impact can be substantial.

The National Academy of Medicine points to a case at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital where they routinely ask about social conditions. An asthma patient told a resident their landlord did not allow an air conditioner.

The hospital referred patient cases like this to Legal Aid. Lawyers there are skilled in finding connections and getting solutions for patients. Together, they discovered 16 patients and Legal Aid clients who had the same landlord. Together, they helped tenants form an association and work with the community to renovate the buildings.

It all started with a hospital gathering routine information and then using community partnerships to impact change.

The doctors didn’t change their focus in the clinic, but a few questions and strong partnerships proved to be the keys to better asthma outcomes.

Healthcare models aimed at improving health outcomes

There’s a movement within the government, health care, insurance industry, and public sector to improve everyone’s health outcomes.

Some of the initiatives include:

- Value-based care reimbursement methodologies and business models such as accountable care organizations (ACOs)

- Accountable Health Communities Model

- Increased flexibility by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to address social and non-medical needs.

- Community health needs assessments for non-profit hospitals every three years

- Social prescribing

There needs to be value in every program, though. As aforementioned, even physicians in value-based care models felt they were not in a position to address SDOH.

The U.S. spends more than most industrialized nations for healthcare relative to social services, yet this country has some of the worst population health outcomes. So, spending more doesn’t mean better outcomes if the spending is not strategic.

SDOH screening tools

While many programs and policy changes make SDOH a priority, the reality is that social needs are usually not met. A recent JAMA study found only 24% of hospitals and 16% of physician practices are screening for the recommended SDOH barriers.

Most clinicians screen for at least one social need, typically interpersonal violence, but not all five factors: food, housing, utility needs, transportation, and interpersonal violence.

While social issues may seem like they’re outside the scope of medicine, they impact the whole person and thus healthcare spending and treatment outcomes. Yet, with limited resources and partnerships, this screening may not be deemed a priority in medical groups.

In the JAMA study, healthcare practices and hospitals cited major barriers to innovation in clinical care. They include lack of resources, incentives, and time.

There are many SDOH toolkits available to assist physicians. Organizations like the National Association of Community Health Centers and the American Medical Association are creating resources to help physicians and hospitals address social needs as part of healthcare.

While physicians can’t solve all of an individual’s problems, they can identify other socioeconomic areas of need and be the catalyst for change.

How can employers address SDOH?

It’s not just a healthcare system problem to solve. Employers have a role too, and with recent social unrest, nearly two-thirds of employers say they will focus on SDOH, according to a Pacific Business Group on Health (PBGH) survey.

In the survey, nearly forty-five percent of respondents said they are revaluating benefit design to “address health system inequities.”

While employers have long-focused on equality – making sure all employees have the same benefits and programs – Castlight says the focus needs to shift to equity. With that perspective, benefits and programs are affordable and accessible to everyone.

When designing health insurance plans and benefit packages, employers should take social needs and concerns into consideration as everyday challenges faced by an employee can impact performance in the office as well as healthcare costs.

The Business Group on Health identifies key programs that can make a difference in SDOH, including tiered premiums, account contributions and/or deductibles based on salary, designing incentives or surcharges that do not disadvantage lower-wage earners, offering prepared take-home meals for purchase, and providing legal assistance when property management issues arise.

Technology can also be leveraged to monitor biometrics, allow better management of chronic conditions, and enhance employees’ engagement in a healthy lifestyle.

Community-based health

As Yang, Pilgrim, and Nwoku point out in an article published in the Wharton Healthcare Quarterly on treating zip codes – a proactive approach focuses on access to healthcare, risks to health and safety such as environmental hazards, and place-based behaviors like diet, exercise, and health screenings.

They consider one study that found the country could save $16 billion annually within five years by just spending $10 a person on community-based public health programs. These programs focus on the basics – physical activity, nutrition, smoking prevention, and tobacco cessation.

Technology provides an opportunity to help achieve health equity, by addressing some of the SDOH.

Transportation is a SDOH that limits access to care. In the Maryland and Washington D.C. area, MedStar partnered with Uber to provide rides so patients can access healthcare facilities when needed. Insurance even pays for it in some cases.

Hospitals are one pillar in the community. They can’t solve the problem on their own. It takes partnerships with other organizations like the YMCA, legal aid, and community health centers to address the needs of patients. Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) can also play a critical role in some communities. Bread for the City is one excellent example.

Holistic healthcare

Coordinated community-based programs can also go a step further and focus on SDOH holistically.

Strategic, multi-sector, place-based partnerships create a holistic structure to reinvest in neighborhoods. The focus is on all the contributing factors – education, housing, healthcare access, and more.

Purpose Built Communities work with local leaders to increase equity and opportunities. Their focus is on racial equity, health outcomes, and economic mobility. Their holistic approach focuses on quality and sustainability with mixed-income housing, community well-being, and a cradle-to-college education pipeline. It’s all implemented by a “community quarterback,” an independent non-profit organization focused solely on revitalizing the neighborhood.

Green space, grocery stores, healthcare facilities, jobs, and educational opportunities are all important.

This model was first applied in East Lake, in southeast Atlanta. First, they focused on housing. Then, education and jobs. Employment for families supported by public assistance programs is up, and the family income quadrupled.

In the absence of holistic approaches, grassroots efforts can also change outcomes.

For example, something as “simple” as volunteering can make a big difference in one’s life, by reducing stress and the risk of heart disease, helping combat depression, and lessening chronic pain. According to the HealthyPeople 2030 report, it can also increase a snese of pride in one’s community.

And voting can make a difference. A study found those who did not vote had poorer health outcomes in subsequent years.

Little changes in approach and consideration of the whole person can make a big difference for an entire community.

COVID-19 and food insecurity

Despite best efforts, it can all can come to a grinding halt when a crisis grips the nation and the world like COVID-19 did.

Food topped the list of unmet needs in the McKinsey survey before the pandemic. It’s only gotten worse.

Despite a number of programs to feed children and reduce food insecurity through school breakfast, lunch, and backpack programs, access was temporarily cut off to these lifelines when schools shut down.

There was an urgent need to feed all the families who relied on these school-based programs and all the new families who suddenly struggled with food insecurity due to lost jobs and other economic pressures from the pandemic.

The government created new distribution channels and new programs to fill this gap, but it took time.

The USDA Farmers to Families Food Box Program distributed more than 47 million free food boxes (which included fresh fruit and vegetables) during COVID-19.

Food insecurity isn’t a problem in isolation. Everything is interconnected. But access to healthy food is a step toward a healthier life and increased potential for better health outcomes.

Structural racism and the impact it has on housing, educational and job opportunities, and access to care all lead to increased risks of getting COVID-19 and dying from it if you’re Black, Latinx, or a member of Indigenous communities.

COVID-19’s impact on Black communities

Black people are dying of COVID-19 at nearly twice (1.9 times) the rate of white people, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

SDOH are a contributing reason for this disparate statistic, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

Poverty, lack of healthcare access, and the impact of discrimination on employment, housing, and education are all factors. Those most at risk are more likely to have an “essential job,” meaning staying at home to minimize risk of exposure to COVID-19 is not an option. They often rely on public transportation, thereby increasing exposure again, and have limited/no access to childcare.

By addressing these barriers to equity holistically, a patchwork network of programs that don’t fully lift a person out of poverty can be avoided.

Addressing SDOH is one step toward health equity, because so many areas are addressed, including economic stability, access to quality education and health care, social and community factors, and of course the neighborhood.

Achieving health equity

Medicine’s effectiveness relies on so much more than what medication, procedures, technology, training, and artificial intelligence can provide.

SDOH impact a patient’s ability to follow a care plan and garner the expected health outcomes.

There are many hurdles to achieving health equity. It requires decreasing health disparities, improving cultural competency and health literacy, and addressing underlying factors, including SDOH.

Until these needs are addressed holistically in a coordinated care plan and valued as much as the latest medication or treatment protocol, we’ll continue to see varying health outcomes that have little to do with medical care and more to do with social determinants of health.